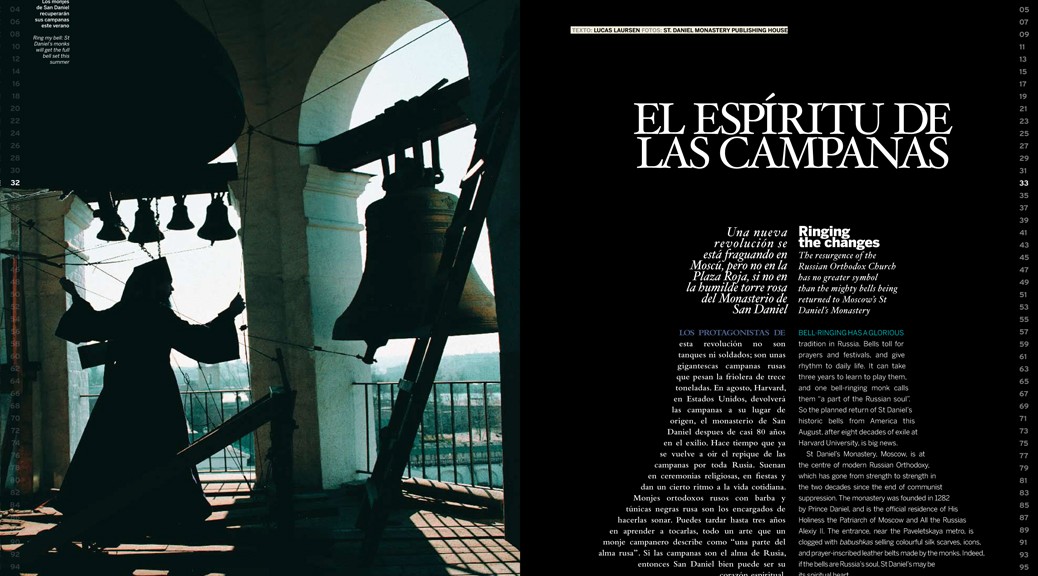

Bell-ringing has a glorious tradition in Russia. Bells toll for prayers and festivals, and give rhythm to daily life. It can take three years to learn to play them, and one bell-ringing monk calls them “a part of the Russian soul.” So the planned return of St Daniel’s historic bells from America this August, after eight decades of exile at Harvard University, is big news.

Bell-ringing has a glorious tradition in Russia. Bells toll for prayers and festivals, and give rhythm to daily life. It can take three years to learn to play them, and one bell-ringing monk calls them “a part of the Russian soul.” So the planned return of St Daniel’s historic bells from America this August, after eight decades of exile at Harvard University, is big news.

St Daniel’s Monastery, Moscow, is at the centre of modern Russian Orthodoxy, which has gone from strength to strength in the two decades since the end of communist suppression. The monastery was founded in 1282 by Prince Daniel, and is the official residence of His Holiness the Patriarch of Moscow and All the Russias Alexiy II. The entrance, near the Paveletskaya metro, is clogged with babushkas selling colourful silk scarves, icons, and prayer-inscribed leather belts made by the monks. Indeed, if the bells are Russia’s soul, St Daniel’s may be its spiritual heart.

But Russia’s soviet rulers were no fans of any ideology other than communism. In 1930, the Soviet government dismantled St Daniel’s monastery, imprisoning monks and severely curtailing the activities of the church. To prevent the destruction of St Daniel’s bells, American businessman Charles Crane bought them and donated them to Harvard University, where they were installed in a student residence.

It was a difficult time for the church, says Roman, a bell ringer at St Daniel’s. “Most of the bells were melted down and the monasteries and churches had only small bells and they couldn’t use those often.”

And it wasn’t just St Daniel’s that came under the soviet kosh. Around the same time, Kazan Cathedral and the Iberian Gates were razed to make room for military parades in Red Square. Bleak decades for Russian Orthodoxy followed. But as the Cold War thawed in the 1980s, relations between church and state grew warmer, and by the early 1990s, the church was restoring a bevy of cathedrals, monasteries, and churches around the country.

“Their interior has been reconstructed very diligently with old Russian-style icons, painting and rich decorations,” says Roman.

Since the 1990s, the church has been steadily recovering other symbols of its lost power, including the famous Mother of God of Kazan icon, returned by the Roman Catholic Pope in 2004. But it’s a private organisation that is funding the return of St Daniel’s bells. The Link of Times Foundation commissioned the casting of a set of replica bells last year. They will take the place of the original bells at Harvard. The bell ringers there will miss the bells they’ve rung for nearly 80 years, but they’re glad the monks will have them, says Jeremy Lin, who adds that the foundation “felt that the bells belonged to the Russian people and should be in Russia”.

When one of the originals was returned in September 2007, parishioners greeted it with kisses, says Roman, “some with tears in their eyes”, and others left flower garlands on the shining bronze bell.

This summer, the bells, which weigh up to 13 tons, will again sound out across Moscow, the Russian soul restored and once more pealing out across the land.

First published by Click Magazine, in both English and Spanish: [pdf].