Pikas in the Pacific Northwest, kiss your privacy goodbye. This spring, Gregg Treinish, wildlife biologist, founder, and director of Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation (ASC), recruited 22 hikers on the Pacific Crest Trail from Campo, California, to Manning Park, British Columbia, to spy on the small, furry mammals. The hikers are recording pika sightings, straw nests, and even urine stains as part of a pilot project to track the impacts of climate change on the creatures. Continue reading Matchmaker, Matchmaker

Pikas in the Pacific Northwest, kiss your privacy goodbye. This spring, Gregg Treinish, wildlife biologist, founder, and director of Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation (ASC), recruited 22 hikers on the Pacific Crest Trail from Campo, California, to Manning Park, British Columbia, to spy on the small, furry mammals. The hikers are recording pika sightings, straw nests, and even urine stains as part of a pilot project to track the impacts of climate change on the creatures. Continue reading Matchmaker, Matchmaker

All posts by LL

Sewer Sampling Reveals Patterns Of Drug Use

While high school graduates in Oslo, Norway, partied hard for two weeks last spring during the so-called Russ graduation festivities, levels of the drug ecstasy spiked about 10-fold in the city’s sewer system, according to new research. In the past few years, water quality specialists have monitored such illicit drug use through sewage sampling there and in other cities, including London and San Diego, to observe the effects of drug control policies.

However, current analytical methods require expensive equipment to collect water samples and don’t allow for continuous sampling of wastewater. Now researchers demonstrate that so-called passive filters provide an efficient and inexpensive means to measure drug use over weeks in municipal wastewater. With the samplers, they studied the ebbs and flows of 11 drugs in Oslo’s sewers for a year, including during the Russ celebrations (Environ. Sci. Technol., DOI: 10.1021/es201124j).

Read the rest of this news item at Chemical & Engineering News [html] or here [pdf]

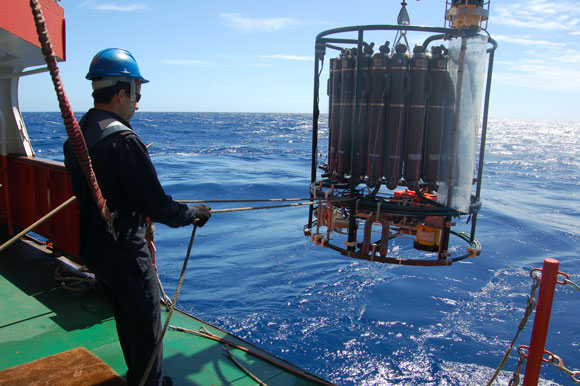

Fieldwork: Close quarters

In the scientists’ lounge aboard the BIO Hespérides one evening last March, Jordi Dachs points at the schedule for the next day’s oceanographic observations. The Spanish research vessel is chugging across the Indian Ocean at a speed of about ten knots. “The storm has put us seven hours behind,” warns Dachs, an environmental chemist at the Institute of Environmental Assessment and Water Research in Barcelona, Spain, whose responsibilities as chief scientist on the ship include planning researchers’ time and instrument use. About two dozen scientists brace themselves against the rhythmic pitching of the vessel. “We might not lower the sampling rosette all the way on some days,” says Dachs, “to save time.”

His suggestion fills the room with tension. Lowering and retrieving the rosette can take many hours, but the water samples it retrieves from the ocean’s depths — as much as 4 kilometres down — hold the biggest potential for new discoveries. Sampling excursions in the Indian Ocean’s deep waters are relatively rare, making the samples particularly valuable.

Fatty Acids In Red Wine Make It Taste Fruity

The quality of a wine is still in the palate of the beholder, but tasters agree that fruitiness is an important contributor. Spanish researchers now report that chemicals responsible for a wine’s foul, sweaty smells also produce its fruity flavor (J. Agric. Food Chem., DOI: 10.1021/jf1048657).

Read the rest of this news brief in Chemical & Engineering News [html] or here [pdf]