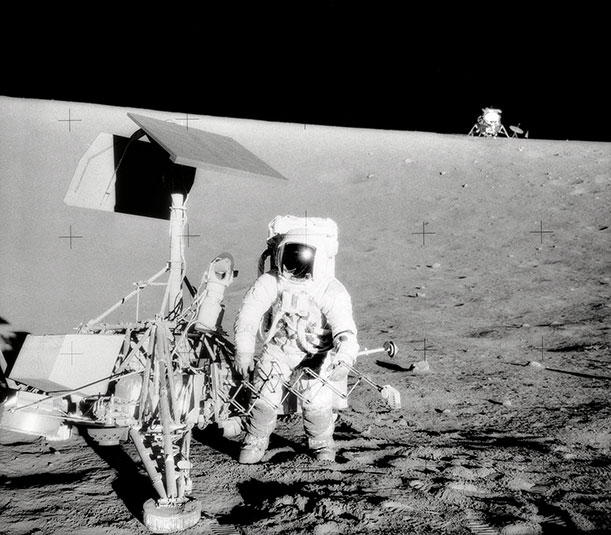

The next several years are shaping up to be busy ones for the moon, with no fewer than 14 landings in the works. That includes the robotic missions soon to be undertaken by five privately funded teams vying for the $20 million Google Lunar XPRIZE, in which the contestants must land a rover on a pre-planned spot, move it at least 500 meters “along an interesting path in a deliberate manner,” and transmit video and other data back to Earth. In fact, tracks from the Google Lunar XPRIZE (GLXP) rovers could be the next intentional tracks to be made by humans on the moon’s surface.

But amid the excitement of exploring the moon, we can’t overlook our lunar heritage, says Derek Webber, a commercial space exploration consultant and former satellite engineer (TEDxBudapest talk: Claiming the future; protecting the past). After all, humanity’s past isn’t just what has been left here on Earth — it’s in space, too. “Lunar heritage is the record of when we first reached the moon, and it captures the epoch-making reality of what happened back then,” he says. New voyagers will encounter 58 years’ worth of human-created artifacts on the moon, including flags and footprints. Here’s why we should be thoughtful about what we do with them. Continue reading How should we protect and preserve our history — on the moon?