When pharmacologist Ravindra Ghooi learned in 1996 that his mother had terminal breast cancer, he began to investigate whether he could obtain morphine, in case she needed pain relief at the end of her life. But a morphine prescription in India at that time, even for the dying, was a rare thing: most states required four or five different licences to buy painkillers such as morphine, and there were harsh penalties for minor administrative errors. Few pharmacies stocked opioids and it was a rare doctor who held the necessary paperwork to prescribe them. Ghooi, who is now a consultant at Cipla Palliative Care and Training Centre in Pune, used his connections to ask government and industry officials if there was a straightforward way of obtaining morphine for his mother. “Everybody agreed to give me morphine,” he recalls, “but they said they’d give it to me illegally.”

Jim Cleary, an oncologist and palliative-care specialist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, has heard similar stories. “Patients with pain have been unwitting victims of the war on drugs,” he says. Opioids have been a hot potato since the 1961 United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. The US-led war on drugs that followed resulted in widespread reluctance to prescribe and supply opioids for fear that patients would become addicted or overdose, or that drug cartels would divert opioids to the black market. Cleary says that countries such as the United States have an “unbalanced” opioid situation, and that abuse in these countries has distorted policies elsewhere, restricting legitimate access.

More than 5 billion people worldwide cannot get the medical opioids that they need. That is a staggering amount of unnecessary agony. “It’s about the government and society at large accepting that while we have a responsibility to prevent abuse and diversion of opiates, we also have a responsibility to people in pain,” says former anaesthesiologist M. R. Rajagopal, who is a founder of palliative-care charity Pallium India in Thiruvananthapuram.

Cleary has been working with activists such as Ghooi and Rajagopal, advocating policies that recognize pain relief as a human right. Such work is slowly reshaping some national drug policies, but changing the status quo entails more than just arguing that patients have a right to opioids — campaigners must also help governments around the world to chart a course to the safe supply of these powerful painkillers.

All sorts of barriers

Many countries have reason to be cautious. In Vietnam, French colonists once promoted opium use to create dependency and enable control of the population. Vietnam now has the highest rate of injection drug use in southeast Asia. In Mexico, the illegal narcotics trade has caused violence, and a level of displacement that approaches that of war zones. It is not surprising, therefore, that people in many countries associate opioids with moral issues, not just medical use.

India’s law governing narcotic drugs was introduced in 1985. It was so strict that there were serious consequences for medical staff or private carers who made errors in record-keeping. Fear of addiction grew — even for people who were dying. By 1998, India’s morphine consumption had dropped by 92%. That year, Ghooi filed a public-interest litigation in the High Court of Delhi, calling for the procedure for the supply of morphine to be simplified. The court eventually ordered Indian states to speed up their opioid-licensing processes.

The ruling in Delhi was only the start. Its impact depended on how fast the 25 states that India had at that time would comply. By 2006, only ten had updated their opioid rules. The following year, Ghooi, Rajagopal and Poonam Bagai — founder of Delhi-based children’s cancer charity CanKids…KidsCan — petitioned India’s Supreme Court, demanding that the central government do more to force the process.

Cleary’s Pain and Policy Studies Group (PPSG) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison is trying another approach. It runs an international fellowship programme that encourages experts from low- and middle-income countries to tackle barriers to opioid use in their own country. In 2012, three Indian palliative-care experts joined the programme, and on return to India began meeting with government officials to discuss a strategy for better opioid access. Working alongside Pallium India, they assisted in drafting an amendment to the law, which was passed in 2014, streamlining opioid permissions to just one licence and shifting powers over drug policy from state to central government.

Cultural barriers are harder to overcome. A 2014 study found that nurses in India rarely recommended prescribing painkillers, even when they thought that the patients needed them, and doctors rarely asked whether they were needed ( et al. Oncologist 19, 515–522; 2014). The study authors described a “culture of non-intervention”.

When it comes to bringing about policy change, the difference between failure and success can depend on the decision of a single government official — and activists must have patience. “I now realize that things change slowly,” Rajagopal says. “Usually, officials change, so I can bide my time and try again.” Nevertheless, Rajagopal is seeing progress. “Good experiences, once made visible, do tend to get replicated elsewhere,” he says. Cities and states are more likely to increase access to opioids and palliative care when they see positive results, without an increase in drug-related problems, in neighbouring regions. By April this year, the situation had changed so much that the Supreme Court of India closed the 2007 case, writing, “the present petition does appear to have served its purpose”.

Different models

The New York-based organization Human Rights Watch has used a similar advocacy approach in its work to reform Mexico’s prescription-opioid regulations. But interim director for health Diederik Lohman says that this is not the only way to change policy. “The other approach is more of an inside game,” he says, and it involves helping ministries and drug regulators to hire palliative- and pain-care specialists who can then work within the organization’s system to offer an international standard of care.

The international non-governmental organization the Global Access to Pain Relief Initiative (GAPRI) has taken this inside approach in Nigeria by supporting a full-time fellow to assist the country’s director of food and drug services with morphine procurement, distribution and usage tracking. This strategy means that “ownership is with the ministry”, Lohman says — the government has a commitment to the programme, making it more likely to succeed.

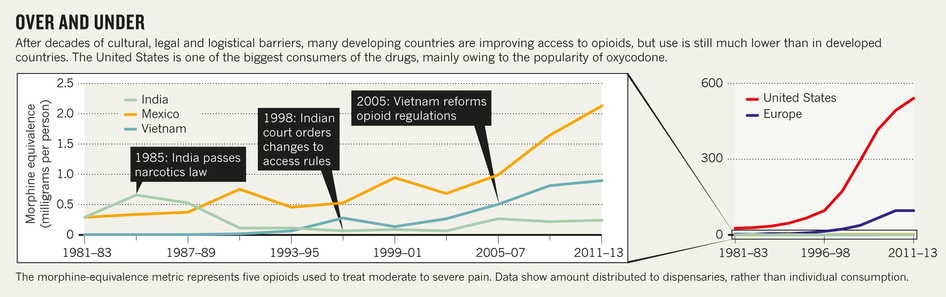

Many palliative-care advocates end up using both strategies. In addition to PPSG’s advocacy work in India, in other countries it has taken an inside-government approach. In 2005, PPSG participated in a palliative-care workshop led by the Vietnamese Ministry of Health. Two of the ministry officials were then invited to complete year-long PPSG fellowships. The officials translated Vietnamese laws surrounding opioid accessibility into English, compared them with World Health Organization guidelines, and drafted new regulations for the Ministry of Health to consider. Since then, opioid consumption in the country has risen nearly 3-fold, from 0.3 mg per person in 2005 to 0.9 mg in 2013 (consumption in the United States in 2013 was more than 500 times higher at 520 mg per person; see ‘Over and under’). Some government officials were already open to reforming the morphine regulations, but the fellowship gave them the opportunity to gather the information they needed to help persuade their colleagues.

Finding consensus

In April, the UN General Assembly held a special session on the world drug problem, which reflected the international community’s slow tilt towards balancing the benefits and risks of opioids. Many countries still want a “drug-free world”, but a growing number have concluded that the war on drugs does not work, Lohman says, and these countries are taking a more public-health-centered approach. Despite the two sides still differing on their drug-control position, the assembly came to a consensus to ensure the availability of controlled substances for medical use. “In that respect, we’ve made a giant leap forward,” Lohman says.

But terminally ill people without access to pain relief may not consider this leap big enough. The UN statement does not constitute legislation, and even in countries, such as India, that have reformed their laws, “legislation does not necessarily mean practice”, Rajagopal says.

Ghooi found that out the hard way when, in 2010, his wife and fellow pharmacologist Shaila also developed cancer. The disease quickly became terminal, but Shaila’s cultural suspicion of opioids meant that even though she was in incredible pain and morphine was readily available, she resisted taking the drug. “My wife grew up in that generation,” recalls Ghooi. She thought that “morphine was too strong an analgesic and she was not ready to take it”, he says. But he thinks that change is coming. “I do feel hopeful that, in five or ten years, at the rate this government is going, things will be better.”

But Rajagopal, who spent 19 years trying to get India’s main narcotics law changed, doesn’t see an end coming soon: “I don’t see any alternative to slow, painstaking work.”

Related links in Nature Research

- Time to connect: bringing social context into addiction neuroscience

- Access to opioid analgesics and pain relief for patients with cancer

- Focus on pain

Related external links